Will training to Heart Rate Zones help your running?

Mark Green

One of the biggest mistakes I see runners make is to do too much of their training too fast. This seems to be a trend across the whole spectrum of runners from complete newbies who have just started running to seasoned professionals who have been running for many years.

To understand what “too fast” means, you first have to understand the difference between running Aerobically or Anaerobically.

AEROBIC TRAINING

Aerobic training essentially means that you are running/training at a low heart rate. It can also be thought of as running at an intensity which would allow you to carry out a conversation. During aerobic running you burn fat as your main source of energy. Aerobic training doesn’t put as much stress on your body as anaerobic training and you don’t need as much recovery time between training sessions, therefore you are less likely to suffer from injury or illness if the bulk of your training is aerobic.

ANAEROBIC TRAINING

Anaerobic training is training at a higher heart rate, or an intensity at which you might only be able to speak two or three words before needing to draw another breath. It essentially means training without oxygen.

Anaerobic training puts a lot more stress on your body. It puts more stress on your muscles and joints because you are running at a faster pace. Anaerobic training sessions, like hill repeats or 1km intervals, take longer for your body to recover from, therefore, your training program needs to be structured to allow enough recovery time after these sessions to minimise the risk of you getting injured or sick.

The bulk of your training (80%) should be done in your aerobic zone.

The aerobic zone will be at a different pace and a different heart rate for different people. For example, someone might be able to run at 4:15min/k with a HR of 144 and be in their aerobic zone, another person might be in their anaerobic zone at 6min/k with a HR of 150.

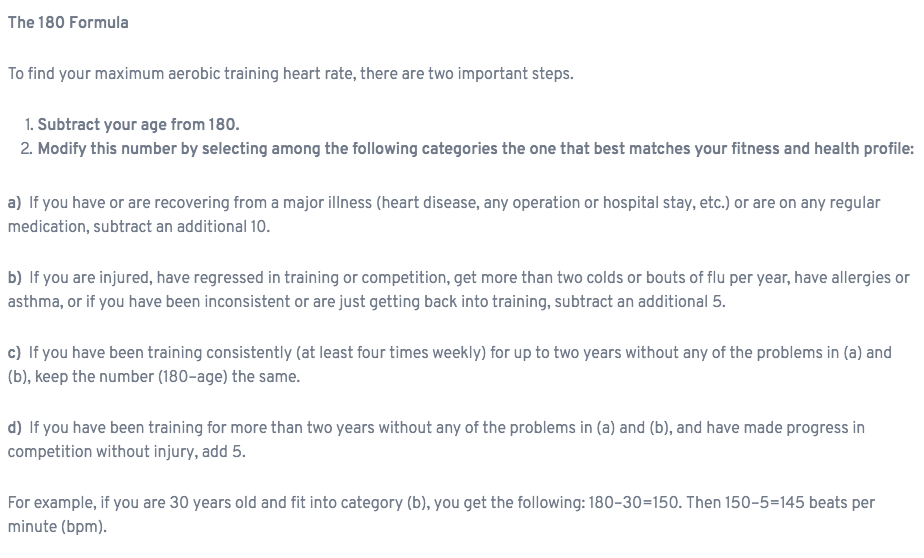

The key to using heart rate as a successful training tool is to find out your individual zones. The most accurate way to do this is to get a lactate threshold test performed by a sports scientist. If you are not yet ready for that level of commitment, there are a number of formulas you can use which will approximate your training zones. In my opinion, the most accurate of these formulas is the 180 Formula which was devised by Phil Maffetone.

Using this 145bpm as an example, it means that your average HR for an aerobic training run should be under 145bpm. It might get to 155 climbing a hill, and be at 135 coming back down the other side, which is OK as long as the average for the whole run stays under 145.

Why not train to pace instead of heart rate?

In road running and triathlon, almost all of the events are on flat terrain, and because of this, most of the training is also on flat terrain. If all of your training is flat, then training at 5min/k’s for example, is reasonably quantifiable. One km is comparable to the next. Therefore you could set up a training plan based on pace and it would be reasonably accurate.

In trail running events however, the terrain is extremely variable. Not only in terms of hills and total elevation, but also in how technical the terrain is. Running at 5min/k’s on an open fire-trail up a 5% gradient, is completely different to running 5min/k’s on a technical single track, even if it is still up a 5% gradient. Because of this variation you can’t quantify how hard a training session is by your pace.

Why not train to “perceived exertion” instead of heart rate?

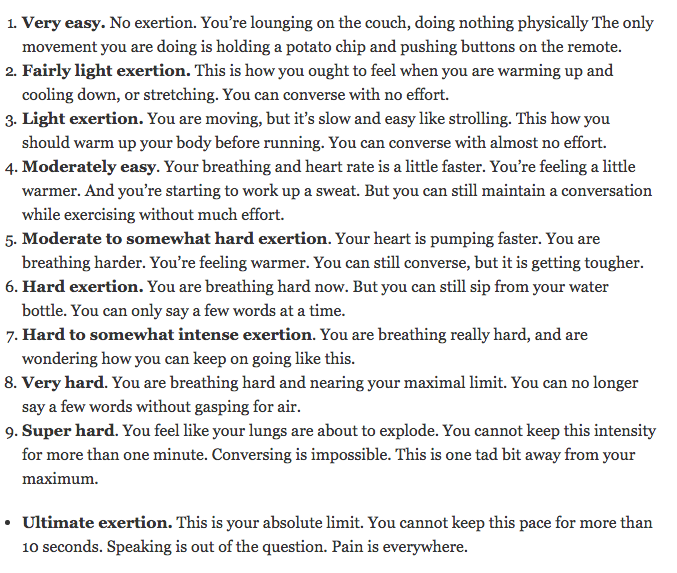

A lot of coaches nowadays have reverted back to the old school method of “Rate of Perceived Exertion – RPE” which basically means that your training pace is dictated by how much effort your are putting in. Here is an example of an RPE scale:

I think that RPE has the potential to be excellent. You don’t need any specialised equipment, you just “run to feel” – the problem however, is that if you have always run “too fast”, then your personal RPE is probably not very accurate. Your “Moderately Easy” zone might be someone else’s “Very Hard” zone, so even if you think you are running aerobically, you’re not.

Another hiccup in using RPE is the relatively recent phenomenon that is social media. Strava in particular. Strava can be a great way of logging your own training and finding out what your mates are doing and giving them some “kudos” for encouragement. Unfortunately, for a lot of runners it also means following some “Elite” athletes and trying to copy what they are doing. “If “John” is running 55km on Sunday at 4min/k’s and he is doing the same race as me, then surely I should be doing that too?”

Trying to keep up with what another runner is doing on Strava is a recipe for disaster full stop. If you are trying to replicate what another runner is doing it means you will be very unlikely to be taking any notice of RPE.

Should you use a Heart Rate Monitor and train to specific Heart Rate Zones?

If you are an experienced road runner or triathlete running on predominantly flat terrain, and you feel like you have a good understanding of how your body works, and how hard you are training, then I think the combination of pace and RPE can be used to quantify your training load to very good effect.

If you are a relative newbie to running (less than 2 years of consistent training), then you need to be aware that your RPE may not yet be finely tuned, and you might inadvertently be doing too much of your training too fast, in which case training to heart rate zones would be very helpful in determining whether your sessions are aerobic or anaerobic.

If you are a trail runner, especially a newcomer, then I think training to heart rate zones is a very good way of monitoring and moderating your training to maximise your training time, and minimise your injury risk.

What should you do next?

If you are interested in trying out heart rate training my first recommendation would be to get a heart rate monitor and use it for a month without actually changing your training. Keep doing your normal sessions and log your maximum HR and average HR for each of your sessions. This will give you some baseline data which can be used later.

After a month, either get a lactate threshold test performed, or use the 180 formula to find out your aerobic threshold, and make sure your “easy” training runs stay in the aerobic zone.

If your aerobic system is not very well developed you might find initially that running aerobically is frustratingly slow. It takes 3 – 4 months of consistent aerobic training to start improving your aerobic system and gaining the benefits. Over these 3 -4 months you will gradually be able to run faster at any given heart rate, which is a sign that your aerobic system is improving.

Think of this as an investment in your long term running health. You need to learn and use a training strategy which ultimately allows you to train as much as you need to, to be able to achieve the goals that you set.